The work of Sheina Marshall FRS on plankton and coral reefs revealed new dimensions of the ocean’s complexity, as Eloise Barber explains.

In 1945, the Royal Society elected its first two female Fellows. Eighty years later, the achievements of women in science continue to inspire, and among the leading lights is Sheina Macalister Marshall (1896-1977). Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1963, Marshall’s work on marine plankton and coral reef ecology revealed new dimensions of the ocean’s complexity and demonstrated the careful observation and perseverance that define groundbreaking research.

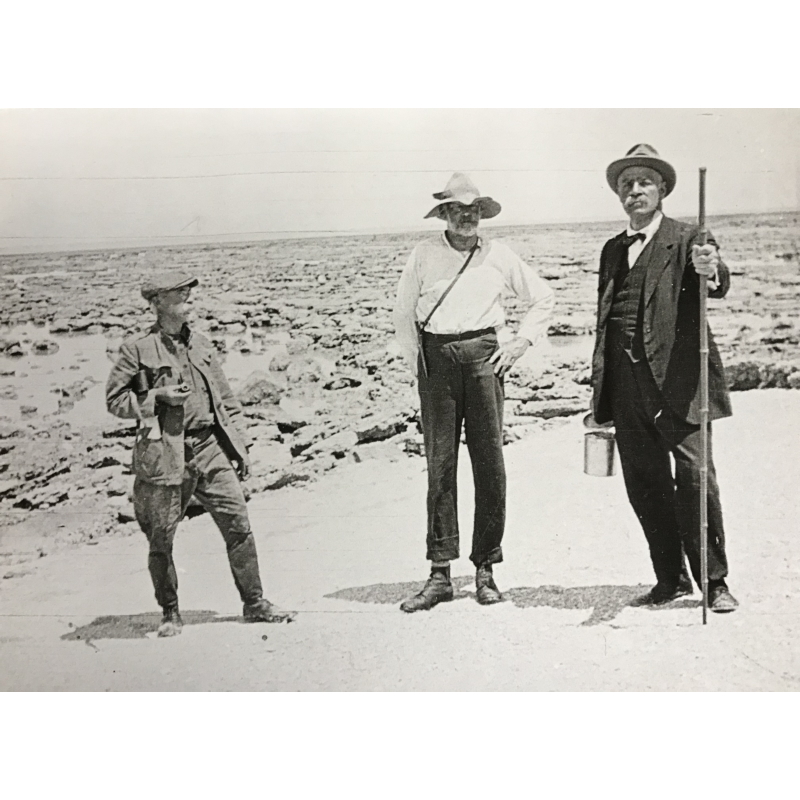

Exposed coral near the anchorage, Low Islands, Queensland, ca. 1928, by C M Yonge (National Library of Australia from Canberra, Australia, no restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons)

Exposed coral near the anchorage, Low Islands, Queensland, ca. 1928, by C M Yonge (National Library of Australia from Canberra, Australia, no restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons)

Marshall was born in Rothesay on the Isle of Bute, the middle of three daughters, in a household steeped in natural history. Her father, a doctor and founder of the Buteshire Natural History Society, encouraged their scientific interests. Childhood rheumatic fever left her frequently bedridden, and she spent long periods reading the works of Charles Darwin, nurturing the curiosity that would shape her life.

She entered the University of Glasgow in 1914 to study zoology, botany and physiology. After a wartime break working in a Balloch radium extraction factory, she returned to complete her studies, graduating with distinction in 1919. A Carnegie Fellowship then allowed her to conduct embryological research under the zoologist John Graham Kerr until 1922.

That year, Marshall joined the Marine Biological Station in Millport as a naturalist, beginning a long collaboration with chemist and oceanographer Andrew Picken Orr. Together they studied plankton in the Clyde and Loch Striven, publishing dozens of papers and several books. In 1934, the University of Glasgow awarded her a Doctor of Science for her work on diatoms and microplankton, cementing her reputation as a leading authority on copepods.

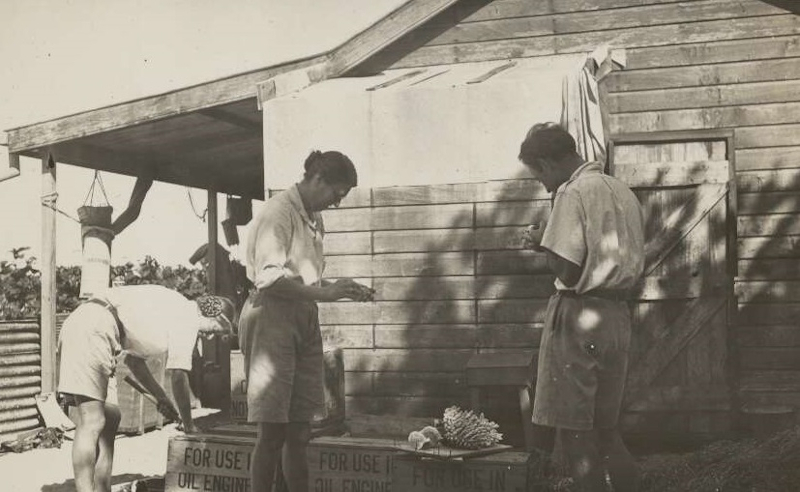

Sheina Marshall & C M Yonge cleaning corals, ca. 1928 (unknown photographer, maybe Frederick Russell, or his wife, Gweneth Russell, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Sheina Marshall & C M Yonge cleaning corals, ca. 1928 (unknown photographer, maybe Frederick Russell, or his wife, Gweneth Russell, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Great Barrier Reef Expedition of 1928–29 was a defining chapter in Marshall’s career. Recommended by Kerr, she joined a twelve-month program led by Charles Maurice Yonge, working with fellow female researchers, including Mattie Yonge, Sidnie Manton and Elizabeth Fraser, making the expedition notable for including women as active contributors. The team also drew on the expertise of local museum staff and Indigenous members of the Yarrabah community. Officially listed as a phytoplankton worker, Marshall carried out a wide range of studies on coral and plankton. Her work combined meticulous microscopic observation with practical laboratory tasks. These included carpentry to construct equipment and furniture, demonstrating her versatility and hands-on approach to field science.

She documented the year-round stability of microplankton in these tropical waters, observing how corals survived and shed sediment in turbid environments, and measuring oxygen production in coral planulae. The team also collected specimens, assessed fish and shellfish populations, and explored economic possibilities for trochus shells and pearl oysters. Press coverage in both Britain and Australia brought marine science to the public, and the expedition’s reports remain foundational in coral physiology.

The village seen through the palms, Badu Island, Queensland, ca. 1928, by C M Yonge (National Library of Australia Commons, no restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons)

The village seen through the palms, Badu Island, Queensland, ca. 1928, by C M Yonge (National Library of Australia Commons, no restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons)

Back in Scotland, Marshall and Orr continued monitoring marine ecosystems in the Clyde. During the Second World War, when global supplies of agar were cut off, Marshall identified False Irish Moss as a suitable British source. She organised large-scale beach collecting efforts by schoolchildren, scouts, and guides. The seaweed was dried and processed at Millport to support bacteriological research and vaccine development.

Recognition of Marshall’s work came gradually. In 1963, as noted, she became a Fellow of the Royal Society, and three years later she was awarded an OBE. She retired as Deputy Director of the Marine Biological Station in 1964 but continued her research, travelled to marine stations abroad, and contributed actively to science well into her seventies.

Marshall died in Millport in 1977, having worked almost to her final day. Her legacy lives on in the plankton species she described, in species named in her honour, including the copepod Calanus marshallae, and in students supported by the Sheina Marshall Memorial Fund. Her life demonstrates how careful observation, rigorous fieldwork and sustained curiosity can illuminate both the smallest marine organisms and the broader systems that sustain life.