Jon Bushell looks at the Edinburgh University artificial intelligence research of Christopher Longuet-Higgins FRS, and the impact on AI of the 1973 Lighthill report.

Artificial intelligence seems to be everywhere at the moment. From the virtual assistants in smartphones to the explosion of generative AI tools in the last few years, you’d be forgiven for viewing this as a twenty-first century phenomenon.

However, the history of scientific research into AI stretches back to Alan Turing’s work in the 1940s on his ‘imitation game’. Today, there’s an ongoing debate about whether the current state of AI represents a true technological leap or a financial bubble. This isn’t a new concern either, as we’ll see from a controversial 1973 report on AI.

In the 1960s Edinburgh was becoming a key hub for artificial intelligence in the UK. One of Turing’s contemporaries at Bletchley Park during the war was Donald Michie, who in 1966 was appointed director of Edinburgh University’s Department of Machine Intelligence and Perception (DMIP). One of the scientists drawn to this newly-established team was Christopher Longuet-Higgins FRS.

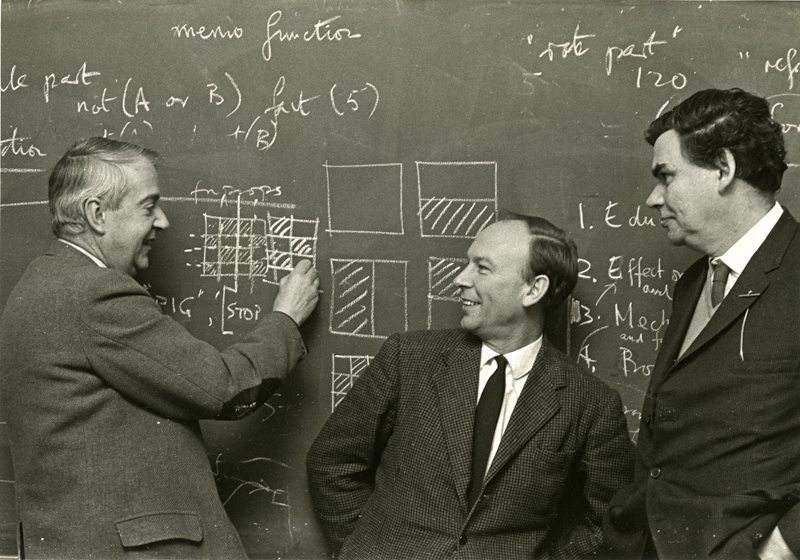

Longuet-Higgins (left) at the Department of Machine Intelligence and Perception in 1968, with Donald Michie (middle) and Richard Gregory (right). From the CLH collection

Longuet-Higgins (left) at the Department of Machine Intelligence and Perception in 1968, with Donald Michie (middle) and Richard Gregory (right). From the CLH collection

Longuet-Higgins’s decision to move to Edinburgh was a surprising one. Far from being a computer scientist, he was a professor of theoretical chemistry at Cambridge. His research into molecular structures had earned him election to the Royal Society in 1958, but in the 1960s he became interested in how the human brain stores and retrieves information. Computers and artificial intelligence were, in Longuet-Higgins’s opinion, useful tools for studying these processes logically. With Richard Gregory FRS, a psychologist also at Cambridge, he hatched a plan to find a university that would support research along these lines, and the DMIP seemed like the perfect fit. The pair moved to Edinburgh in 1967 after enthusiastic and encouraging discussions with Michie.

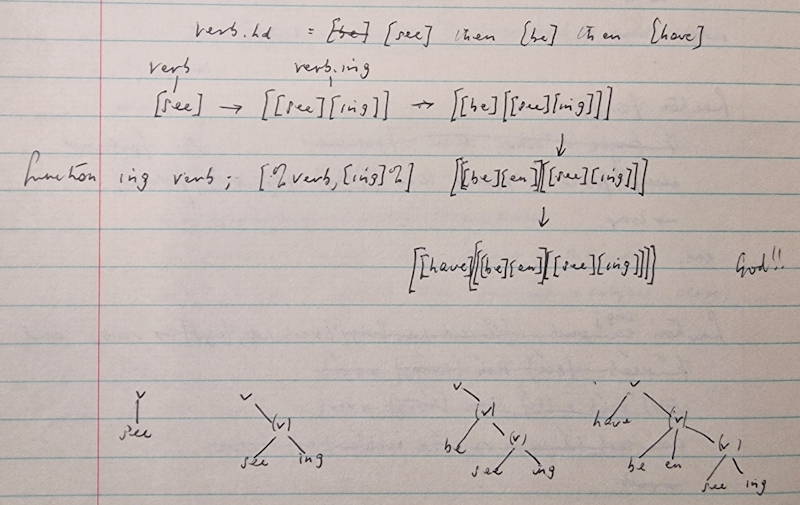

Diagram from Longuet-Higgins’s notebook (CLH/1/1)

Diagram from Longuet-Higgins’s notebook (CLH/1/1)

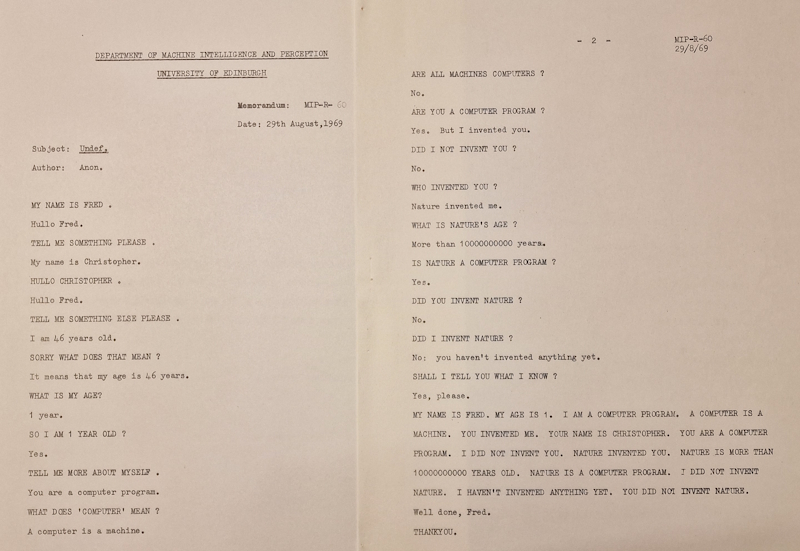

To support his new role, Longuet-Higgins was appointed as a Royal Society Research Professor in 1968, a position he held until his retirement in 1988. His initial focus was on computer memory and recall, attempting to simulate these processes as they occurred in the human mind, and on creating computer programs which could understand music and the semantics of the English language. One of Longuet-Higgins’s early projects was a computer-assisted typewriter, which demonstrated a very rudimentary form of predictive text. His department was also testing interactions with a computer using simple question-and-answer inputs.

A ’conversation piece’ between Longuet-Higgins and a machine called Fred (from CLH/4/7)

A ’conversation piece’ between Longuet-Higgins and a machine called Fred (from CLH/4/7)

Despite the commendable scientific output of the DMIP, problems were beginning to arise behind the scenes. Gregory, who had been working on bionics research, departed Edinburgh in 1970, after securing funding from the Medical Research Council to establish the Brain and Perception Laboratory in Bristol. Gregory’s departure was a heavy blow because he had also taken on the role of Department Chair at Edinburgh, handling many of the necessary routine duties.

The question of who should take on the resulting administrative burden was one reason for a growing friction within the department, exacerbated by competition for access to computer equipment. Matters became sufficiently serious that Edinburgh University considered moving Longuet-Higgins’s research group to a new department, independent of the DMIP.

Internal conflicts weren’t the only threat to artificial intelligence at Edinburgh. A sizable grant from the Science Research Council (SRC) had helped fund the establishment of the DMIP in the 1960s. However, by the early 1970s the SRC was concerned that UK-based AI research wasn’t delivering the promised results. They commissioned mathematician Sir James Lighthill FRS, who was not an expert in the field, to write a report on the state of AI in the UK.

By selecting an outsider, the SRC’s stated intention was to get an unbiased view of AI, supposedly supporting better funding decisions in the rapidly expanding field. How truly independent this report was is a matter of some debate. The two main centres for AI research at the time were Edinburgh and Sussex, and both were pushing for more funding to procure expensive computer hardware from the United States. It seems the SRC held some concerns about the costs of such a move – Jon Agar’s excellent paper on the Lighthill report highlights that Lighthill was given quite a strong steer regarding expectations for the report’s findings.

Sir James Lighthill (Royal Society Photographic Collections, IM/002749)

Sir James Lighthill (Royal Society Photographic Collections, IM/002749)

Regardless of how much this influenced Lighthill, his conclusions were clear. Studies on factory automation had produced tangible gains, and psychology and neurology had also benefitted from incorporating the use of computers. In these cases, AI was being used as a tool to enhance and support scientific investigation, but Lighthill was far more dismissive about ‘pure’ research into artificial intelligence itself. In his view, most of the work in this area was focused on the goal of building intelligent robots, and had achieved little in the way of results. Lighthill’s report was sceptical to the point that he expressed ‘doubts about whether the whole concept of AI as an integrated field of research is a valid one.’

The SRC gave several scientists working on AI, including both Longuet-Higgins and Michie, the chance to critique Lighthill’s conclusions. Unsurprisingly, Michie’s response took issue with Lighthill’s dismissive recommendations. He wrote an impassioned defence of the work taking place at Edinburgh, while also trying to make the case for an increase in funding to ensure adequate computer hardware was available in Britain.

Longuet-Higgins, however, was firmly on Lighthill’s side. He had always been clear in his view that AI was a tool to assist with understanding the brain, rather than a worthwhile avenue of research on its own. In his response to the report, Longuet-Higgins coined the term ‘cognitive science’ to describe this type of work, and throughout his career was more comfortable being described as a cognitive scientist than as an AI researcher.

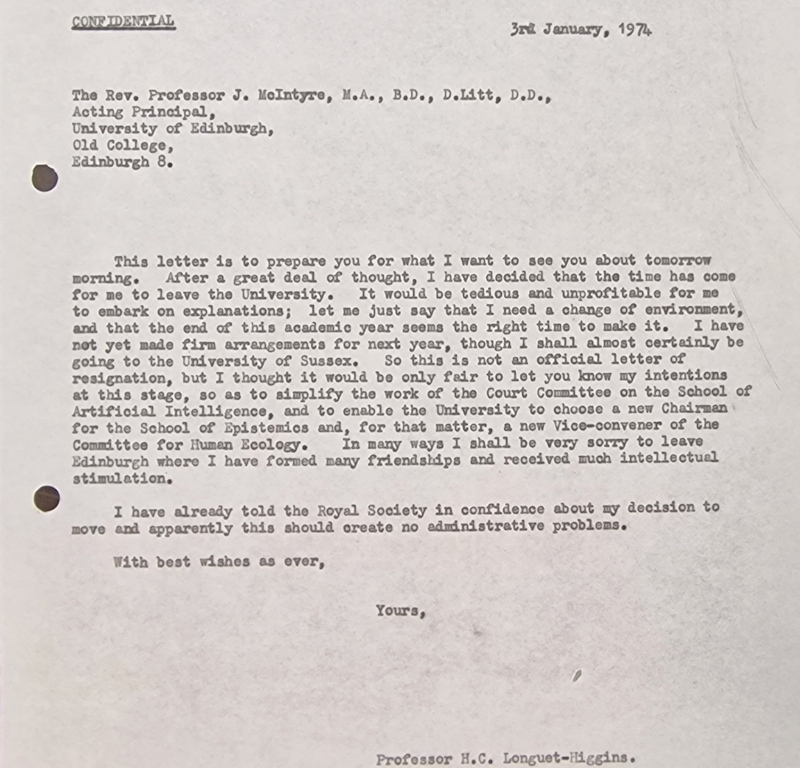

Letter from Longuet-Higgins, informing Edinburgh University of his intention to resign and move to Sussex (from CLH/11/26)

Letter from Longuet-Higgins, informing Edinburgh University of his intention to resign and move to Sussex (from CLH/11/26)

The impact of the Lighthill report was seismic, and funding for basic AI research in Britain dried up quickly as a result. Longuet-Higgins’s decision not to defend the work of the DMIP certainly can’t have helped his relationship with Michie, and probably hastened his move to Sussex University in 1974, where he continued to make significant contributions to the field. This included his work on algorithms for computer vision, which laid the groundwork for much of the image recognition technology in use today. Not bad going for a scientist with a background in chemistry!