What does the Royal Society Library want for Christmas? Keith Moore lists some stocking fillers to plug the gaps in our printed book collections.

What does the Royal Society Library want for Christmas? I’m glad you asked me that, because I’m fascinated by gaps in our collections and it would be great to have some of these stocking fillers. Why did some Fellows of the Royal Society donate their books and others not? There are clues to their reasoning in some cases, but still, when we do identify ‘missing’ items, the Library team tries to acquire the books concerned. Some are unusual, rare, or just downright expensive. Let’s see what Santa might have in his book-sack for us this year.

I suppose what got me thinking about this was noticing the recent news that the Cornish language, Kernewek, was being given the highest level of protected status as a minority language. The Royal Society’s eighteenth-century Fellow, Daines Barrington (1727/8-1800), published the pre-emptive ‘On the expiration of the Cornish language’ in 1779; but not with the Royal Society, as with his study of the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, but with the Society of Antiquaries instead. In this case, I can understand why we might not have a contemporary offprint from Archaeologia, since the two societies and their respective libraries were housed side-by-side in the North Wing of Somerset House from 1780. But it would be nice to have a copy, all the same.

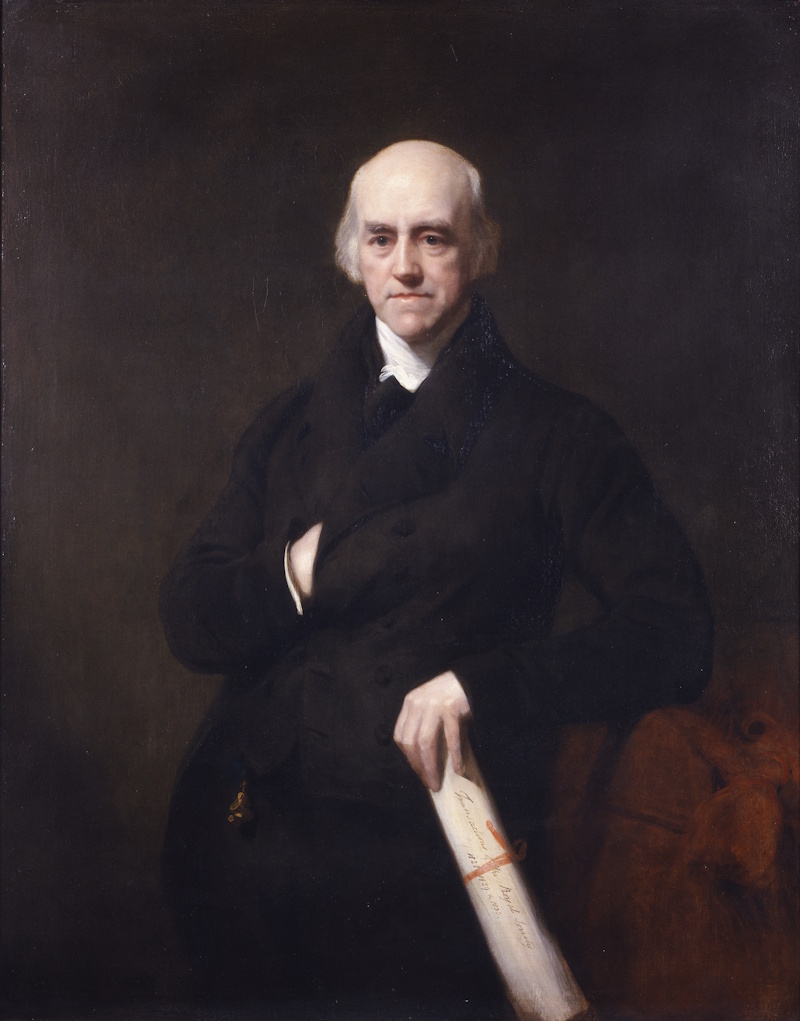

Portrait of Davies Gilbert, by Thomas Phillips, 1833 (RS.9710)

Portrait of Davies Gilbert, by Thomas Phillips, 1833 (RS.9710)

Staying in that part of the country, and in this season, it would be lovely to find a good imprint of Some ancient Christmas carols, with the tunes to which they were formerly sung in the West of England (1822). The editor, Davies Gilbert FRS (1767-1839), may have been an eminent President of the Royal Society, but he gathered these seasonal songs as he was ‘anxious […] to preserve them on account of the delight they afforded him in childhood; when the festivities of Christmas Eve were anticipated by many days of preparation’. The collection carefully curated the music and lyrics to ‘Whilst shepherds watched their flocks by night’, so the subsequent textual outrages committed by generations of schoolchildren may not have been to Gilbert’s purpose. I suppose that Gilbert would not have considered such a book sufficiently scientific to warrant a donation to the Royal Society Library, but it is a measure of the influence of Fellows in unexpected fields – and therefore definitely one to have.

Christmas is a time for a little over-indulgence, so I was distressed to see that we have only one book by the most authoritative nineteenth-century example of nominative determinism, William Kitchiner (1778-1827). Kitchiner is a bit of a special case for the Royal Society, in that he was proposed for the Fellowship (he wrote on telescopes) and moved in Fellowship circles, but oddly, he was not elected. Because we missed him as a Fellow, we must have missed his writings too. These chart his career as a chef and food expert and, like Gilbert, he was partial to musical accompaniments – he would play piano to welcome guests to his ‘experimental’ dinners.

Kitchiner’s books of recipes, kitchen management, and healthy lifestyles were runaway bestsellers of the Romantic era; and although he is little known these days, he does have a certain kind of fame in being the first to write down a recipe for potato crisps (recipe no.104 in The cook’s oracle, since you ask). His turkey preparation method might be a little too gruesome for this vegetarian’s modern sensibilities but I’ll leave you to judge the gentleman cook’s labours: ‘never dress it till at least four or five days after it has been killed […] hang it up by four of the large tail feathers, and when, on paying his morning visit to the Larder, he finds it lying upon a cloth, prepared to receive it when it falls, that day let it be cooked’.

Obviously, we’ll be needing a little champagne with that, and although we have the manuscript version (above) of ‘Some observations concerning the ordering of wines’ (1662) by Christopher Merrett FRS, we lack the printed version of the paper. This is often found as an addendum to the second part of Walter Charleton’s Two discourses (1669), which deals with 'the mysterie of vintners'. We’ve acquired several of Charleton’s ‘missing in action’ books in recent years, but that’s one we still have to find. Merrett’s discourse to the Royal Society, outlining the English claim to the double fermentation method of making sparkling wine, was recently covered in The Times, thanks to the Sorbonne’s Jean-Robert Pitte scandalising the French wine industry.

Wild turkey cock, hen and young, by John James Audubon. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Wild turkey cock, hen and young, by John James Audubon. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Of course, if you really want to spoil us, the book to get would be The birds of America (1827-1838) by John James Audubon FRS (1785-1851). Even on the flat page this most handsome series of ornithology plates contains a livelier-looking wild turkey than William Kitchiner’s cook-up version. The ‘Birds’ comes in the largest of elephant folio editions, so tricky to get into our library Christmas stocking, and at auction highs of $10 million and more, it’s enough to give even the most hardened book lover a case of indigestion.

Therefore, I’ll leave you with a section of William Kitchiner’s poetic farewell to his readers, and some sound Christmas advice:

Restrain each forward appetite,

To dine with prudence and delight,

And carefully all our rules to follow,

To masticate before they swallow.

Tis thus Hygeia guides our pen,

To warn the greedy sons of men

To moderate their wine and meat,

And ‘Eat to live, not live to eat.’

Restraint doesn’t apply to books of course – you can’t have too many.